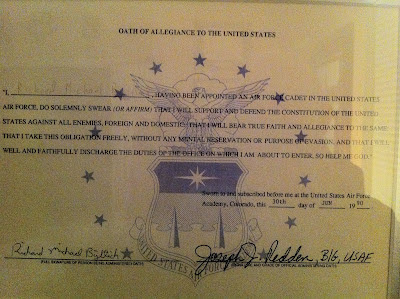

Twenty-two years ago today I flew to Colorado Springs, CO and reported for Basic Cadet Training with the class of 1994 at the United States Air Force Academy. I took the oath of office pictured at left the following day. I left the service in 2001 because I could no longer fit my military intelligence and computer network defense career interests within the archaic, central planning commission-like personnel system the ruled Air Force assignments.

Today I read an article by Tim Kane, USAFA class of 1990, titled Why Our Best Officers Are Leaving. This article resonated so strongly with me I got a little emotional reading it. The following are some relevant excerpts.

Why are so many of the most talented officers now abandoning military life for the private sector? An exclusive survey of West Point graduates shows that it’s not just money. Increasingly, the military is creating a command structure that rewards conformism and ignores merit. As a result, it’s losing its vaunted ability to cultivate entrepreneurs in uniform...

The military’s problem is a deeply anti-entrepreneurial personnel structure. From officer evaluations to promotions to job assignments, all branches of the military operate more like a government bureaucracy with a unionized workforce than like a cutting-edge meritocracy...

In a recent survey I conducted of 250 West Point graduates (sent to the classes of 1989, 1991, 1995, 2000, 2001, and 2004), an astonishing 93 percent believed that half or more of “the best officers leave the military early rather than serving a full career.”

Why is the military so bad at retaining these people? It’s convenient to believe that top officers simply have more- lucrative opportunities in the private sector, and that their departures are inevitable. But the reason overwhelmingly cited by veterans and active-duty officers alike is that the military personnel system—every aspect of it—is nearly blind to merit. Performance evaluations emphasize a zero-defect mentality, meaning that risk-avoidance trickles down the chain of command.

Promotions can be anticipated almost to the day— regardless of an officer’s competence—so that there is essentially no difference in rank among officers the same age, even after 15 years of service.

Job assignments are managed by a faceless, centralized bureaucracy that keeps everyone guessing where they might be shipped next...

When I asked veterans for the reasons they left the military, the top response was “frustration with military bureaucracy”—cited by 82 percent of respondents (with 50 percent agreeing strongly)...

In a 2007 essay in the Armed Forces Journal, Lieutenant Colonel Paul Yingling offered a compelling explanation for this risk-averse tendency. A veteran of three tours in Iraq, Yingling articulated a common frustration among the troops: that a failure of generalship was losing the war. His critique focused not on failures of strategy but on the failures of the general-officer corps making the strategy, and of the anti-entrepreneurial career ladder that produced them:

“It is unreasonable to expect that an officer who spends 25 years conforming to institutional expectations will emerge as an innovator in his late forties.”

[A]n internal job market might be the key to revolutionizing military personnel. In today’s military, individuals are given “orders” to report to a new assignment every two to four years. When an Army unit in Korea rotates out its executive officer, the commander of that unit is assigned a new executive officer. Even if the commander wants to hire Captain Smart, and Captain Smart wants to work in Korea, the decision is out of their hands—and another captain, who would have preferred a job in Europe, might be assigned there instead.

The Air Force conducts three assignment episodes each year, coordinated entirely by the Air Force Personnel Center at Randolph Air Force Base, in Texas. Across the globe, officers send in their job requests. Units with open slots send their requirements for officers. The hundreds of officers assigned full-time to the personnel center strive to match open requirements with available officers (each within strictly defined career fields, like infantry, intelligence, or personnel itself), balancing individual requests with the needs of the service, while also trying to develop careers and project future trends, all with constantly changing technological tools. It’s an impossible job, but the alternative is chaos.

In fact, a better alternative is chaos. Chaos, to economists, is known as the free market, where the invisible hand matches supply with demand...

Here is how a market alternative would work. Each commander would have sole hiring authority over the people in his unit. Officers would be free to apply for any job opening. If a major applied for an opening above his pay grade, the commander at that unit could hire him (and bear the consequences). Coordination could be done through existing online tools such as monster.com or careerbuilder.com (presumably those companies would be interested in offering rebranded versions for the military). If an officer chose to stay in a job longer than “normal” (“I just want to fly fighter jets, sir”), that would be solely between him and his commander...

I surveyed ex-military officers at Citi, Dell, Amazon, Procter & Gamble, TMobile, Amgen, Intuit, and countless venture-capital firms. At every company, the veterans were shocked to look back at how “archaic and arbitrary” talent management was in the armed forces. Unlike industrial-era firms, and unlike the military, successful companies in the knowledge economy understand that nearly all value is embedded in their human capital.

I completely agree with this article, especially the concepts of an "internal market" for hiring and retaining talent. I hope someone with the power to implement change reads Mr Kane's article and fights the bureaucracy to improve all the military services by nurturing their most important resource: people.

0 komentar:

Posting Komentar